The Complete Guide to Software Engineering: Building a Successful Career in Modern Software Development

The technology landscape is evolving at an unprecedented pace, and software engineering stands at the forefront of this digital revolution. Whether you’re a aspiring developer taking your first steps into coding or an experienced professional looking to advance your career, understanding the comprehensive landscape of software engineering is essential for long-term success in the tech industry.

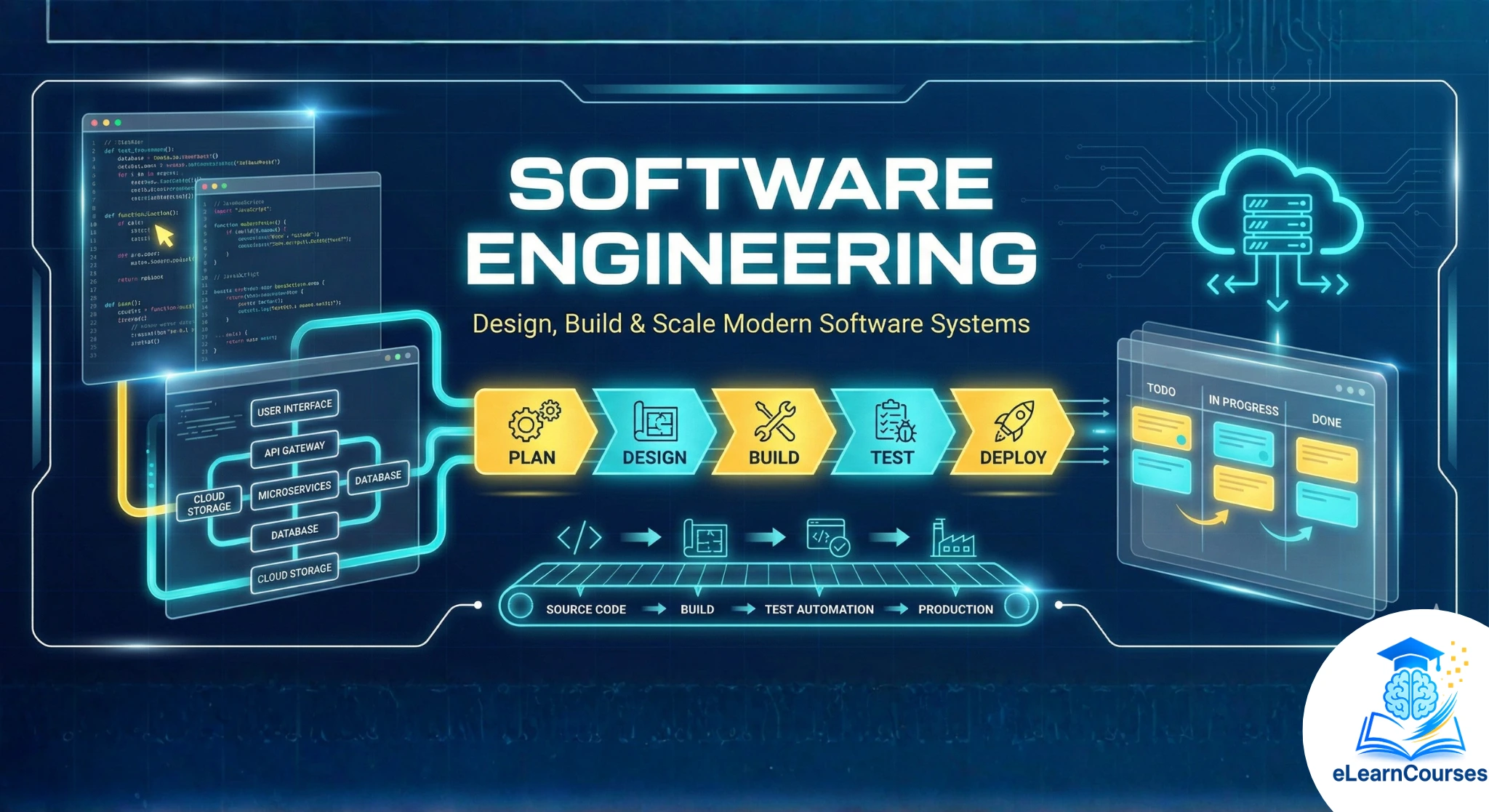

Software engineering represents far more than just writing code—it encompasses a systematic, disciplined approach to designing, developing, testing, and maintaining software systems that solve real-world problems. This field combines computer science principles, engineering practices, and creative problem-solving to build the applications, platforms, and systems that power our modern world.

Understanding Software Engineering: Foundations and Core Concepts

What Defines Software Engineering?

Software engineering is the application of engineering principles to software development in a methodical way. Unlike casual programming, software engineering involves structured methodologies, rigorous testing protocols, and systematic approaches to creating scalable, maintainable, and efficient software solutions.

The distinction between programming and software engineering lies in scope and methodology. While programming focuses on writing code to solve specific problems, software engineering encompasses the entire software development lifecycle—from initial concept and requirements gathering through design, implementation, testing, deployment, and ongoing maintenance.

The Evolution of Software Development Practices

The journey of software engineering has been marked by continuous innovation and adaptation. From the early days of procedural programming to today’s cloud-native architectures, the field has evolved through several paradigm shifts:

Early Computing Era: Software development began as a highly specialized activity performed by computer scientists working directly with machine code and assembly language. Programs were simple, monolithic, and tightly coupled to specific hardware configurations.

Structured Programming Movement: The introduction of structured programming brought discipline to code organization through the use of functions, loops, and conditional statements, replacing the chaotic “spaghetti code” of earlier approaches.

Object-Oriented Revolution: Object-oriented programming introduced concepts of encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism, enabling developers to model real-world entities and relationships more naturally in code.

Agile Transformation: The shift from waterfall to agile methodologies revolutionized how teams approach software development, emphasizing iterative progress, continuous feedback, and adaptive planning.

Modern DevOps Era: Today’s software engineering landscape embraces DevOps practices, continuous integration and deployment, microservices architectures, and cloud-native development approaches.

Core Principles That Guide Software Engineering

Several fundamental principles underpin effective software engineering practices:

Modularity and Separation of Concerns: Breaking complex systems into smaller, manageable components makes software easier to understand, test, and maintain. Each module should have a single, well-defined responsibility.

Abstraction and Information Hiding: Hiding implementation details behind well-defined interfaces allows developers to work with complex systems at appropriate levels of abstraction, reducing cognitive load and improving code maintainability.

Code Reusability: Writing reusable components and following the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle minimizes redundancy and accelerates development while improving consistency across applications.

Scalability and Performance: Designing systems that can handle growing workloads efficiently requires careful consideration of algorithms, data structures, caching strategies, and system architecture.

Security by Design: Incorporating security considerations from the earliest stages of development helps protect systems against vulnerabilities and data breaches.

Essential Technical Skills for Software Engineering Success

Programming Languages and Their Ecosystems

Mastery of programming languages forms the foundation of software engineering expertise. While the specific languages you choose depend on your career focus, understanding multiple languages and their paradigms makes you a more versatile developer.

General-Purpose Languages: Python has become one of the most popular languages for software engineering due to its readability, extensive libraries, and versatility across web development, data science, automation, and artificial intelligence applications. JavaScript remains essential for web development, powering both frontend interfaces through frameworks like React and Vue, and backend services through Node.js.

Systems Programming: Languages like C++ and Rust excel in scenarios requiring low-level control, high performance, and efficient memory management. These languages are crucial for operating systems, game engines, embedded systems, and performance-critical applications.

Enterprise Development: Java and C# dominate enterprise software development with their robust ecosystems, strong typing systems, and extensive frameworks for building large-scale business applications.

Modern Alternatives: Go (Golang) has gained popularity for building microservices and cloud-native applications due to its simplicity, built-in concurrency support, and efficient compilation. Kotlin has become the preferred language for Android development, while Swift dominates iOS development.

Data Structures and Algorithms Mastery

Understanding data structures and algorithms represents a cornerstone of software engineering competency. These concepts directly impact your ability to write efficient, scalable code that performs well under real-world conditions.

Fundamental Data Structures: Arrays, linked lists, stacks, queues, hash tables, trees, and graphs each serve specific purposes and offer different performance characteristics. Knowing when to use each structure is crucial for optimal solution design.

Algorithm Design Paradigms: Divide and conquer, dynamic programming, greedy algorithms, backtracking, and branch and bound represent powerful approaches to problem-solving. Understanding these paradigms enables you to tackle complex computational challenges effectively.

Complexity Analysis: Big O notation helps you analyze and compare algorithm efficiency in terms of time and space complexity, enabling informed decisions about which approach to use for specific problems.

Practical Applications: Sorting algorithms, searching techniques, graph traversal methods, and string manipulation algorithms form the building blocks of many real-world applications from database indexing to route optimization in navigation systems.

Software Architecture and Design Patterns

Software architecture defines the high-level structure of software systems, while design patterns provide reusable solutions to common design problems.

Architectural Patterns: Monolithic architecture suits smaller applications with simpler requirements, while microservices architecture enables independent development, deployment, and scaling of individual service components. Event-driven architecture facilitates loose coupling and asynchronous communication between system components.

Creational Patterns: Singleton, Factory, Builder, and Prototype patterns address object creation mechanisms, increasing flexibility and reusability of code.

Structural Patterns: Adapter, Decorator, Facade, and Proxy patterns deal with object composition and relationships, simplifying complex system structures.

Behavioral Patterns: Observer, Strategy, Command, and State patterns define communication patterns between objects and the distribution of responsibilities.

SOLID Principles: Single Responsibility, Open-Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, and Dependency Inversion principles guide object-oriented design toward more maintainable and flexible systems.

The Software Development Lifecycle in Practice

Requirements Engineering and Analysis

Successful software engineering projects begin with thorough requirements gathering and analysis. This phase establishes what the software should accomplish and sets expectations for all stakeholders.

Functional Requirements: These specify what the system should do—the features, capabilities, and behaviors that users expect. Clear functional requirements prevent misunderstandings and scope creep during development.

Non-Functional Requirements: Performance benchmarks, security standards, scalability targets, usability criteria, and compliance requirements fall into this category. These often prove just as important as functional requirements for project success.

Stakeholder Communication: Effective software engineers excel at translating business needs into technical specifications while managing expectations and maintaining clear communication channels with product managers, designers, and end users.

Requirements Documentation: Creating comprehensive yet accessible documentation ensures all team members share a common understanding of project goals and specifications.

System Design and Planning

The design phase transforms requirements into detailed technical specifications and architectural blueprints that guide implementation.

High-Level Design: System architecture decisions, technology stack selection, infrastructure planning, and integration strategies are established during high-level design. These decisions have long-lasting implications for system maintainability and scalability.

Low-Level Design: Detailed component specifications, database schemas, API contracts, and class diagrams provide specific guidance for implementation work.

Database Design: Proper database design involves normalization to reduce redundancy, index optimization for query performance, and careful consideration of relationships between entities.

API Design: RESTful principles, GraphQL schemas, or gRPC service definitions establish contracts between system components and external consumers.

Implementation Best Practices

Writing clean, maintainable code requires discipline and adherence to established best practices within the software engineering community.

Code Quality Standards: Consistent formatting, meaningful naming conventions, appropriate commenting, and adherence to language-specific style guides improve code readability and maintainability.

Version Control: Git has become the de facto standard for version control, enabling collaboration, change tracking, and code review workflows. Understanding branching strategies, pull requests, and merge conflict resolution is essential.

Code Reviews: Peer review processes catch bugs early, spread knowledge across teams, maintain code quality standards, and promote collaborative improvement.

Documentation: Inline comments explain complex logic, README files provide project overviews, API documentation describes interfaces, and architectural decision records capture important design choices.

Testing and Quality Assurance

Comprehensive testing strategies ensure software reliability, catch bugs early, and enable confident refactoring and feature additions.

Unit Testing: Testing individual components in isolation verifies that each piece functions correctly. Test-driven development (TDD) advocates writing tests before implementation code.

Integration Testing: These tests verify that different components work together correctly, catching issues that arise from interactions between modules.

End-to-End Testing: Full workflow testing from user perspective ensures the complete system functions as expected in real-world scenarios.

Performance Testing: Load testing, stress testing, and scalability testing identify bottlenecks and verify that systems meet performance requirements under various conditions.

Security Testing: Penetration testing, vulnerability scanning, and security audits protect against common attack vectors and ensure compliance with security standards.

Modern Software Engineering Methodologies

Agile Development Frameworks

Agile methodologies have transformed software engineering by emphasizing flexibility, collaboration, and iterative progress over rigid planning and documentation.

Scrum Framework: This popular agile framework organizes work into time-boxed sprints, typically lasting two weeks. Daily standup meetings, sprint planning sessions, sprint reviews, and retrospectives create a rhythm of continuous improvement.

Kanban Method: Visualizing work in progress through kanban boards helps teams manage flow, identify bottlenecks, and limit work in progress to maintain focus and productivity.

Extreme Programming: XP emphasizes technical practices like pair programming, continuous integration, test-driven development, and simple design to improve code quality and team collaboration.

Agile Values: Individuals and interactions over processes and tools, working software over comprehensive documentation, customer collaboration over contract negotiation, and responding to change over following a plan guide agile software engineering teams.

DevOps and Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment

DevOps culture bridges the gap between development and operations teams, emphasizing collaboration, automation, and shared responsibility for software quality and reliability.

Continuous Integration: Automatically building and testing code changes as they’re committed catches integration issues early and maintains code quality. CI servers like Jenkins, GitLab CI, and GitHub Actions automate this process.

Continuous Deployment: Automating the deployment pipeline enables frequent, low-risk releases. Infrastructure as code, containerization with Docker, and orchestration with Kubernetes facilitate consistent, repeatable deployments.

Monitoring and Observability: Production monitoring, logging, tracing, and alerting provide visibility into system health and performance, enabling rapid identification and resolution of issues.

Site Reliability Engineering: SRE practices apply software engineering principles to infrastructure and operations problems, emphasizing automation, measurement, and continuous improvement.

Cloud-Native Development

Modern software engineering increasingly targets cloud platforms, leveraging their scalability, reliability, and managed services.

Cloud Service Models: Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) provides virtual machines and networking, Platform as a Service (PaaS) abstracts infrastructure management, and Software as a Service (SaaS) delivers complete applications.

Serverless Architecture: Functions as a Service (FaaS) platforms like AWS Lambda enable developers to focus on code rather than server management, with automatic scaling and pay-per-execution pricing.

Container Orchestration: Kubernetes has become the standard for managing containerized applications at scale, handling deployment, scaling, networking, and service discovery.

Cloud-Native Patterns: Circuit breakers, bulkheads, retries with exponential backoff, and other resilience patterns help build robust distributed systems.

Specializations Within Software Engineering

Frontend Development

Frontend software engineering focuses on creating user interfaces and user experiences that are intuitive, responsive, and accessible.

Modern Frameworks: React, Vue, and Angular dominate the frontend landscape, each offering different approaches to building component-based user interfaces. Understanding component lifecycle, state management, and rendering optimization is crucial.

Responsive Design: Creating interfaces that work seamlessly across devices requires understanding CSS flexbox and grid layouts, media queries, and mobile-first design principles.

Web Performance: Optimizing loading times through code splitting, lazy loading, image optimization, and caching strategies directly impacts user experience and business metrics.

Accessibility: Following WCAG guidelines ensures applications are usable by people with disabilities, which is both ethically important and legally required in many jurisdictions.

Backend Development

Backend software engineering involves building server-side logic, databases, APIs, and infrastructure that power applications.

API Development: RESTful services, GraphQL endpoints, and gRPC services enable communication between frontend clients and backend systems. Understanding HTTP protocols, authentication mechanisms, and API versioning is essential.

Database Management: Relational databases like PostgreSQL and MySQL excel at structured data with complex relationships, while NoSQL databases like MongoDB and Cassandra suit unstructured data and high-scale scenarios.

Caching Strategies: Redis and Memcached reduce database load and improve response times by storing frequently accessed data in memory.

Message Queues: RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka, and AWS SQS enable asynchronous processing and decouple system components, improving scalability and resilience.

Also Read: C Programming Tutorial

Full Stack Development

Full stack software engineers possess expertise across both frontend and backend technologies, enabling them to build complete applications independently.

Technology Stacks: Popular combinations include MEAN (MongoDB, Express, Angular, Node.js), MERN (MongoDB, Express, React, Node.js), and LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP) stacks.

Integration Skills: Full stack developers excel at connecting frontend interfaces to backend services, managing data flow, and ensuring consistent user experiences.

System Thinking: Understanding how different layers interact enables better architectural decisions and more effective troubleshooting.

Mobile Development

Mobile software engineering targets smartphones and tablets, with distinct platforms requiring specialized knowledge.

Native Development: Swift for iOS and Kotlin for Android provide full access to platform capabilities and optimal performance but require maintaining separate codebases.

Cross-Platform Frameworks: React Native, Flutter, and Xamarin enable code sharing across platforms while maintaining near-native performance and user experience.

Mobile-Specific Challenges: Limited screen real estate, touch interfaces, varying network conditions, battery consumption, and platform-specific design guidelines shape mobile development practices.

Data Engineering and Machine Learning

The intersection of software engineering and data science creates opportunities to build systems that process, analyze, and learn from large datasets.

Data Pipelines: ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) processes move data between systems, clean and transform it, and prepare it for analysis or machine learning.

Big Data Technologies: Apache Spark, Hadoop, and distributed computing frameworks handle datasets too large for single machines.

ML Engineering: Deploying machine learning models to production requires software engineering discipline around versioning, monitoring, retraining pipelines, and serving infrastructure.

MLOps: Applying DevOps practices to machine learning workflows ensures reliable, reproducible model development and deployment.

Career Development in Software Engineering

Educational Pathways

Multiple routes lead to successful software engineering careers, each with distinct advantages and challenges.

Computer Science Degrees: Traditional four-year degrees provide comprehensive theoretical foundations, covering algorithms, data structures, computer architecture, operating systems, and software engineering principles. This deep understanding supports long-term career growth and complex problem-solving.

Bootcamps and Accelerated Programs: Intensive coding bootcamps compress practical skills into 12-24 week programs, focusing on job-ready skills and portfolio development. These suit career changers and those seeking faster entry into the field.

Self-Taught Path: Online resources, tutorials, documentation, and practice projects enable motivated individuals to learn software engineering independently. This path requires exceptional discipline and self-direction but proves highly cost-effective.

Continuous Learning: Regardless of initial training, successful software engineers commit to lifelong learning, staying current with evolving technologies, frameworks, and best practices.

Building Your Technical Portfolio

A strong portfolio demonstrates practical skills and problem-solving abilities to potential employers.

Personal Projects: Building complete applications from concept to deployment showcases your ability to work independently and make technical decisions. Choose projects that solve real problems or demonstrate specific technologies you want to highlight.

Open Source Contributions: Contributing to open source projects demonstrates collaboration skills, code quality, and community engagement. Start with documentation improvements or bug fixes before tackling larger features.

Technical Writing: Blog posts, tutorials, and documentation writing showcase your ability to communicate complex technical concepts clearly—a valuable skill for any software engineer.

GitHub Profile: A well-maintained GitHub profile with readable code, meaningful commit messages, and comprehensive README files serves as your professional portfolio.

Soft Skills for Software Engineering Excellence

Technical expertise alone doesn’t guarantee career success—soft skills significantly impact your effectiveness and advancement opportunities.

Communication: Explaining technical concepts to non-technical stakeholders, writing clear documentation, and participating effectively in meetings are daily requirements for software engineers.

Collaboration: Modern software engineering is inherently collaborative. Working effectively in teams, conducting constructive code reviews, and contributing to team culture are essential skills.

Problem-Solving: Breaking down complex problems, evaluating alternatives, and making pragmatic trade-offs between competing concerns define effective software engineering.

Time Management: Balancing multiple priorities, estimating task complexity accurately, and meeting deadlines while maintaining code quality requires discipline and experience.

Adaptability: Technology changes rapidly. Embracing new tools, frameworks, and methodologies while maintaining productivity separates thriving engineers from those who stagnate.

Career Progression and Specialization

Software engineering careers offer diverse progression paths beyond traditional management tracks.

Individual Contributor Track: Senior Engineer, Staff Engineer, Principal Engineer, and Distinguished Engineer roles provide advancement opportunities while remaining focused on technical work.

Technical Leadership: Tech leads and architects guide technical direction, make architectural decisions, and mentor other engineers while remaining involved in implementation.

Engineering Management: Engineering managers focus on people leadership, team building, project planning, and cross-functional collaboration while maintaining technical credibility.

Product Management Transition: Software engineers often transition into product management, leveraging technical understanding to bridge user needs and technical feasibility.

Entrepreneurship: Engineering skills provide a foundation for building startups or consulting businesses, enabling you to create solutions directly addressing market needs.

Emerging Trends Shaping Software Engineering

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

AI is transforming software engineering both as a tool for developers and as a component within applications.

AI-Assisted Development: GitHub Copilot, ChatGPT, and similar tools augment developer productivity by suggesting code completions, generating boilerplate, and explaining complex code.

Intelligent Applications: Embedding machine learning capabilities into applications enables features like personalized recommendations, natural language processing, computer vision, and predictive analytics.

AutoML and Low-Code: Automated machine learning platforms and low-code development environments democratize advanced capabilities, though deep software engineering knowledge remains essential for complex scenarios.

Edge Computing and IoT

Computing is shifting closer to data sources, creating new opportunities and challenges for software engineers.

Edge Processing: Processing data near its source reduces latency and bandwidth requirements, enabling real-time applications like autonomous vehicles and industrial automation.

IoT Ecosystems: Billions of connected devices generate massive data streams requiring specialized software to collect, process, and act upon information.

Resource Constraints: Developing for edge devices requires optimization skills and understanding of hardware limitations, power consumption, and connectivity challenges.

Quantum Computing

While still emerging, quantum computing represents a paradigm shift with profound implications for certain problem domains.

Quantum Algorithms: Solving specific optimization, simulation, and cryptography problems exponentially faster than classical computers requires fundamentally different algorithmic approaches.

Hybrid Systems: Practical applications will likely combine classical and quantum computing, requiring software engineers who understand both paradigms.

Preparing for the Future: While widespread adoption remains years away, forward-thinking engineers are beginning to explore quantum programming frameworks and concepts.

Blockchain and Distributed Systems

Blockchain technology extends beyond cryptocurrency into supply chain management, digital identity, and decentralized applications.

Smart Contracts: Self-executing contracts on blockchain platforms require careful software engineering to avoid vulnerabilities and ensure correct execution.

Decentralized Applications: Building applications without central authorities introduces unique challenges around consensus, data consistency, and user experience.

Security Considerations: Immutability and transparency create both opportunities and challenges for software engineers working with blockchain systems.

Challenges and Considerations in Software Engineering

Technical Debt Management

Technical debt—the implied cost of additional rework caused by choosing quick solutions over better approaches—accumulates in most software projects.

Recognizing Technical Debt: Code duplication, poor documentation, outdated dependencies, missing tests, and architectural shortcuts all contribute to technical debt.

Balancing Trade-offs: Sometimes accepting technical debt makes business sense to meet deadlines or test market hypotheses. The key is conscious decision-making and planning for eventual remediation.

Refactoring Strategies: Regular refactoring prevents technical debt from becoming overwhelming. Allocating time for code quality improvements maintains long-term velocity.

Security and Privacy Concerns

Software engineers bear responsibility for protecting user data and system integrity against increasingly sophisticated threats.

Common Vulnerabilities: SQL injection, cross-site scripting (XSS), cross-site request forgery (CSRF), and insecure authentication mechanisms remain prevalent despite being well-understood.

Security Best Practices: Input validation, parameterized queries, proper authentication and authorization, encryption of sensitive data, and regular security audits form a foundation of secure software engineering.

Privacy Regulations: GDPR, CCPA, and other privacy regulations impose legal requirements on data handling, requiring software engineers to implement privacy-by-design principles.

Scalability and Performance

Building systems that gracefully handle growth requires foresight and architectural discipline.

Horizontal vs Vertical Scaling: Adding more machines (horizontal scaling) typically provides better scaling characteristics than upgrading existing machines (vertical scaling) but introduces complexity.

Caching Strategies: Multi-level caching from CDNs to application-level caches dramatically improves performance and reduces infrastructure costs.

Database Optimization: Query optimization, proper indexing, connection pooling, and database sharding enable databases to handle growing workloads.

Load Balancing: Distributing traffic across multiple servers improves reliability and performance while enabling rolling deployments.

Conclusion: Your Software Engineering Journey

Software engineering offers intellectually stimulating work, excellent career prospects, and the opportunity to create solutions that impact millions of users worldwide. Whether you’re building mobile applications, designing distributed systems, training machine learning models, or architecting cloud infrastructure, software engineering skills open doors to diverse opportunities.

Success in this field requires combining technical expertise with soft skills, maintaining curiosity about new technologies while mastering fundamentals, and balancing pragmatism with quality. The most effective software engineers never stop learning, embrace challenges as growth opportunities, and find satisfaction in solving complex problems through elegant code.

The field rewards those who invest in continuous improvement, contribute to communities, and approach problems with both creativity and rigor. As you progress in your software engineering career, remember that technology serves people—the best engineers maintain focus on creating value and solving real problems rather than pursuing complexity for its own sake.

Your journey in software engineering is unique, shaped by your interests, strengths, and opportunities. Whether you specialize deeply in one area or maintain broad expertise across the stack, whether you lead teams or contribute as an individual expert, the skills you develop will remain valuable throughout your career. The software engineering landscape will continue evolving, bringing new challenges and opportunities, but the fundamental principles of clear thinking, clean code, and user-focused design endure.

Embrace the journey, build things that matter, and join the community of software engineers shaping our digital future.