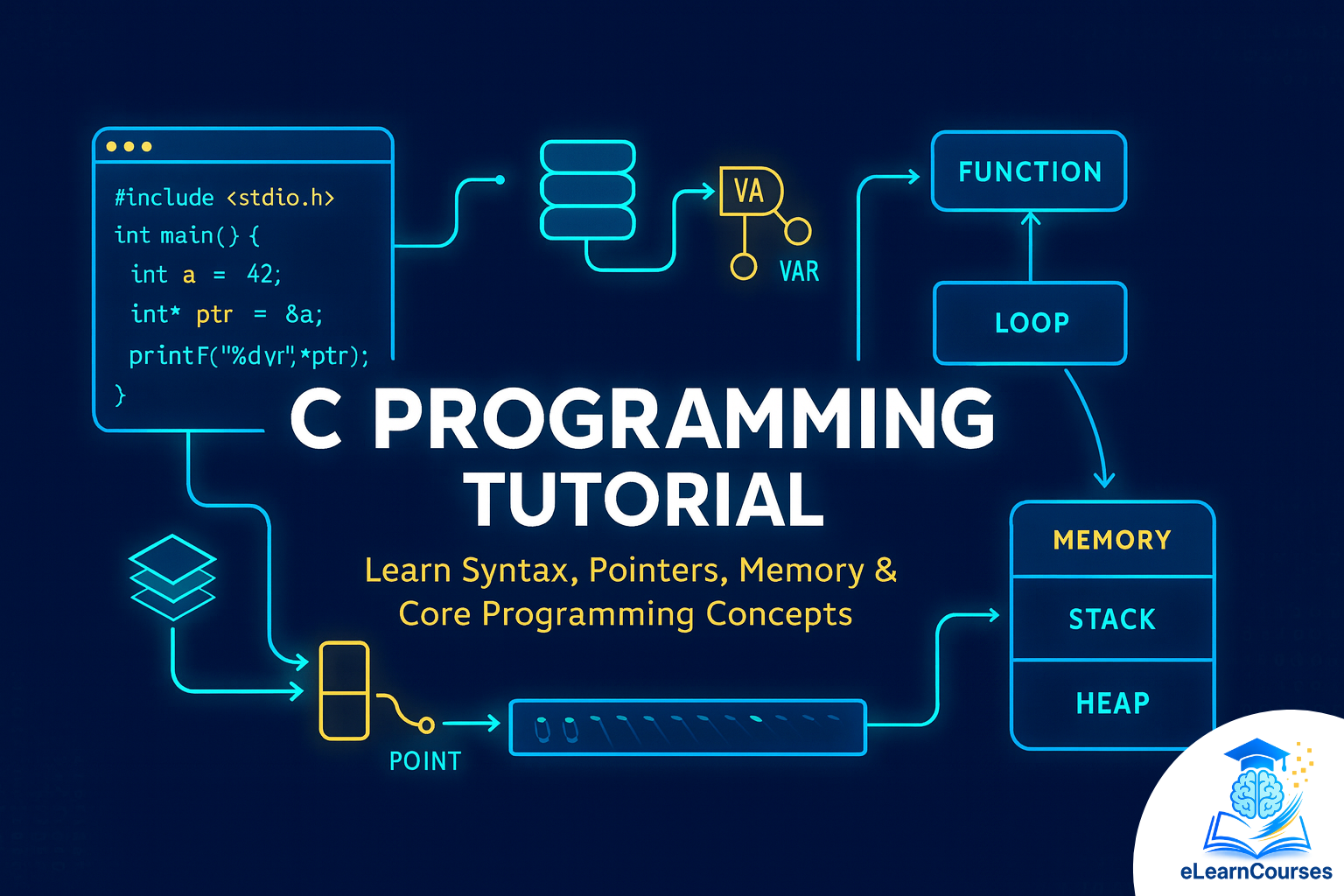

Master C Programming Tutorial: Ultimate Guide for Beginners & Experts

C programming remains one of the most powerful and influential programming languages in software development. Whether you’re a complete beginner or looking to strengthen your programming foundation, this comprehensive C programming tutorial will guide you through everything you need to know about C language development.

In this detailed C programming tutorial, you’ll discover fundamental concepts, practical coding techniques, and advanced programming strategies that professional developers use daily. By the end of this guide, you’ll have the knowledge and confidence to write efficient C programs and understand why C continues to power operating systems, embedded systems, and high-performance applications worldwide.

Introduction to C Programming

What is C Programming?

C is a general-purpose, procedural programming language developed by Dennis Ritchie at Bell Labs in 1972. This C programming tutorial begins with understanding why C has remained relevant for over five decades. C provides low-level access to memory, requires minimal runtime support, and generates efficient machine code, making it ideal for system programming and embedded applications.

Why Learn C Programming?

Learning C programming offers numerous advantages for aspiring developers:

Foundation for Modern Languages: Many popular programming languages like C++, Java, Python, and JavaScript draw inspiration from C syntax and concepts. Understanding C programming helps you grasp these languages more easily.

System-Level Programming: Operating systems like Linux, Windows kernels, and Unix are written primarily in C. This C programming tutorial will help you understand how software interacts with hardware at a fundamental level.

Performance-Critical Applications: C generates highly optimized code, making it perfect for applications where performance matters, including game engines, database systems, and real-time applications.

Embedded Systems Development: Microcontrollers and embedded devices predominantly use C due to its efficiency and direct hardware manipulation capabilities.

Career Opportunities: C programming skills remain highly valued in industries ranging from aerospace to automotive, telecommunications to finance.

Brief History of C Language

The evolution of C programming is fascinating. Dennis Ritchie developed C at Bell Laboratories between 1972 and 1973 to construct utilities running on Unix. Initially, C was designed for implementing the Unix operating system, but its power and flexibility quickly made it popular for application development.

The first major milestone came in 1978 when Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie published “The C Programming Language,” often referred to as K&R C. This book became the de facto specification for C until the official ANSI standard emerged.

In 1989, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standardized C, creating ANSI C or C89. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) adopted this standard in 1990, creating C90. Subsequent revisions including C99, C11, and C17 added new features while maintaining backward compatibility.

Setting Up Your C Development Environment

Before diving deeper into this C programming tutorial, you need to set up your development environment properly. A complete C development setup includes a compiler, text editor or IDE, and debugger.

Choosing a C Compiler

GCC (GNU Compiler Collection): The most widely used open-source compiler, available on Linux, macOS, and Windows through MinGW or Cygwin. GCC provides excellent optimization and follows C standards strictly.

Clang: Modern compiler with excellent error messages and fast compilation times. Clang is the default compiler on macOS and increasingly popular on other platforms.

Microsoft Visual C++: Integrated with Visual Studio, MSVC offers excellent Windows development support and debugging tools.

Tiny C Compiler (TCC): Lightweight and fast compiler suitable for learning and quick compilation.

Installing Development Tools

On Windows: Download and install MinGW-w64 or use Visual Studio Community Edition. MinGW provides a complete GNU toolchain including GCC, while Visual Studio offers an integrated development environment with comprehensive debugging capabilities.

On macOS: Install Xcode Command Line Tools by running xcode-select --install in Terminal. This provides GCC, Clang, and essential development utilities.

On Linux: Most distributions include GCC by default. Install using package managers: sudo apt-get install build-essential on Ubuntu/Debian or sudo yum groupinstall "Development Tools" on Red Hat/CentOS.

Recommended Text Editors and IDEs

Visual Studio Code: Free, lightweight editor with excellent C/C++ extensions providing IntelliSense, debugging, and code formatting.

Code::Blocks: Cross-platform IDE specifically designed for C/C++ with integrated debugger and project management.

CLion: Professional IDE from JetBrains offering advanced refactoring, code analysis, and debugging features.

Vim/Emacs: Powerful text editors preferred by experienced developers for their efficiency and customization options.

Verifying Your Installation

After installation, verify your setup by creating a simple test program. Open your terminal or command prompt and type gcc --version to confirm GCC installation. This C programming tutorial recommends testing with the classic “Hello World” program to ensure everything works correctly.

Basic Syntax and Structure

Understanding C program structure is fundamental to this C programming tutorial. Every C program follows specific organizational patterns that ensure proper compilation and execution.

Structure of a C Program

A typical C program contains several components:

Preprocessor Directives: Lines beginning with # that provide instructions to the preprocessor before compilation. Common directives include #include for including header files and #define for defining constants.

Function Declarations: Prototypes that inform the compiler about functions used in the program.

Main Function: The entry point of every C program where execution begins.

Statements and Expressions: Actual code that performs operations and manipulations.

Comments: Non-executable text that explains code functionality.

Here’s a basic program structure:

#include <stdio.h> // Preprocessor directive

// Function declaration

void greet();

// Main function

int main() {

printf("Welcome to C Programming Tutorial\n");

greet();

return 0;

}

// Function definition

void greet() {

printf("Hello, Programmer!\n");

}Comments in C Programming

Comments make code readable and maintainable. C supports two comment styles:

Single-line comments use double slashes // and extend to the end of the line. These are perfect for brief explanations.

Multi-line comments begin with /* and end with */, spanning multiple lines. Use these for detailed explanations or temporarily disabling code blocks.

Effective commenting is a professional practice covered throughout this C programming tutorial. Good comments explain why code does something, not what it does, as the code itself should be self-explanatory.

Input and Output Functions

C provides several functions for input and output operations:

printf(): Formatted output function that displays text and variables to the console. It accepts format specifiers like %d for integers, %f for floating-point numbers, and %s for strings.

scanf(): Formatted input function that reads user input according to specified format. Always use address-of operator & with variables in scanf for proper memory access.

getchar() and putchar(): Character-level input and output functions for single character operations.

gets() and puts(): String input and output functions, though gets() is deprecated due to security concerns.

Compilation Process

Understanding compilation helps debug issues in this C programming tutorial. The C compilation process involves four stages:

Preprocessing: The preprocessor handles directives, expands macros, and includes header files, producing an expanded source file.

Compilation: The compiler translates expanded source code into assembly language, checking syntax and performing optimizations.

Assembly: The assembler converts assembly code into machine code, creating object files.

Linking: The linker combines object files with library code, resolving external references and producing the final executable.

Data Types and Variables

Data types define the kind of data a variable can store and the operations that can be performed on it. This section of our C programming tutorial explores C’s type system comprehensively.

Basic Data Types

Integer Types: C provides several integer types with varying sizes and ranges:

int typically stores 4 bytes (32 bits) and can represent values from approximately -2 billion to +2 billion. Use int for general-purpose integer arithmetic.

short int uses 2 bytes, suitable for memory-constrained situations requiring smaller integer ranges.

long int provides at least 4 bytes, with long long int guaranteeing 8 bytes for very large integers.

unsigned variants store only positive values, effectively doubling the positive range by eliminating negative numbers.

Floating-Point Types: For decimal numbers, C offers:

float provides single-precision floating-point representation with approximately 6-7 decimal digits of precision, using 4 bytes.

double offers double-precision with 15-16 decimal digits of precision, using 8 bytes. This is the default choice for floating-point calculations.

long double provides extended precision, though exact size and precision vary by implementation.

Character Type: The char type stores single characters and small integers, occupying 1 byte. Characters use ASCII encoding on most systems, with values ranging from -128 to 127 for signed char or 0 to 255 for unsigned char.

Variable Declaration and Initialization

Variables must be declared before use, specifying their type and name. This C programming tutorial emphasizes proper variable naming conventions:

int age; // Declaration

age = 25; // Assignment

int count = 10; // Declaration with initialization

float price = 99.99; // Floating-point initialization

char grade = 'A'; // Character initialization

// Multiple variables of same type

int x = 5, y = 10, z = 15;Variable Naming Rules:

- Names must begin with letters or underscores

- Subsequent characters can be letters, digits, or underscores

- Case-sensitive (age and Age are different variables)

- Cannot use C keywords as variable names

- Use descriptive names for readability

Type Modifiers

Modifiers alter the properties of basic data types:

signed: Allows both positive and negative values (default for most types)

unsigned: Restricts to non-negative values only, doubling positive range

short: Reduces storage size

long: Increases storage capacity

These modifiers combine with basic types: unsigned long int, signed char, etc.

Constants and Literals

Constants represent fixed values that don’t change during program execution. This C programming tutorial covers several constant types:

Integer Literals: Whole numbers like 42, -17, or 0. Use suffixes L or LL for long integers, U for unsigned.

Floating-Point Literals: Decimal numbers like 3.14, -0.5, or 2.5e3 (scientific notation). Suffix F denotes float, default is double.

Character Literals: Single characters in single quotes like ‘A’, ‘7’, or ‘\n’ (newline escape sequence).

String Literals: Sequences of characters in double quotes like “Hello World”.

Defining Constants:

#define PI 3.14159 // Preprocessor constant

const int MAX_SIZE = 100; // Constant variableType Conversion

Type conversion happens explicitly (casting) or implicitly (automatic):

Implicit Conversion: When assigning a value of one type to a variable of another type, C automatically converts if possible. Smaller types convert to larger types without data loss.

Explicit Conversion (Casting): Programmers force conversion using cast operators:

float result = (float)sum / count; // Convert sum to float before division

int truncated = (int)3.99; // Converts to 3, losing decimal partOperators in C Programming

Operators perform operations on variables and values. This comprehensive C programming tutorial section covers all operator categories.

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators perform mathematical calculations:

Addition (+): Adds two operands Subtraction (-): Subtracts second operand from first Multiplication (*): Multiplies two operands Division (/): Divides first operand by second (integer division truncates decimal) Modulus (%): Returns remainder after division (works only with integers)

int a = 15, b = 4;

int sum = a + b; // 19

int difference = a - b; // 11

int product = a * b; // 60

int quotient = a / b; // 3 (integer division)

int remainder = a % b; // 3Increment and Decrement:

Pre-increment ++x increments then returns value, while post-increment x++ returns value then increments. Same logic applies to decrement operators.

Relational Operators

Relational operators compare values, returning 1 (true) or 0 (false):

Equal to (==): Checks if operands are equal Not equal to (!=): Checks if operands differ Greater than (>): Tests if first exceeds second Less than (<): Tests if first is smaller than second Greater than or equal to (>=): Tests first is at least as large as second Less than or equal to (<=): Tests first is at most as large as second

Logical Operators

Logical operators combine boolean expressions:

Logical AND (&&): Returns true if both operands are true Logical OR (||): Returns true if at least one operand is true Logical NOT (!): Reverses the boolean value

int x = 5, y = 10;

if (x > 0 && y > 0) { // Both conditions must be true

printf("Both positive\n");

}Bitwise Operators

Bitwise operators work on individual bits of integer values, crucial for low-level programming covered in this C programming tutorial:

AND (&): Sets each bit to 1 if both corresponding bits are 1 OR (|): Sets each bit to 1 if at least one corresponding bit is 1 XOR (^): Sets each bit to 1 if corresponding bits differ NOT (~): Inverts all bits Left Shift (<<): Shifts bits left, filling with zeros Right Shift (>>): Shifts bits right

Bitwise operations are essential for embedded programming, cryptography, and optimization tasks.

Assignment Operators

Assignment operators assign values to variables:

Simple assignment (=): Assigns right operand to left operand Compound assignments: Combine arithmetic with assignment: +=, -=, *=, /=, %=

int num = 10;

num += 5; // Equivalent to num = num + 5

num *= 2; // Equivalent to num = num * 2Conditional (Ternary) Operator

The ternary operator provides a compact conditional expression:

int max = (a > b) ? a : b; // If a > b, max = a, otherwise max = bThis C programming tutorial recommends using ternary operators for simple conditions to improve code conciseness.

Operator Precedence and Associativity

Understanding operator precedence prevents logical errors. Operators execute in order of precedence, with parentheses having highest priority. When operators have equal precedence, associativity determines evaluation order (left-to-right or right-to-left).

Control Flow Statements

Control flow statements determine program execution path based on conditions and loops. This critical C programming tutorial section explains decision-making and iteration.

Conditional Statements

if Statement: Executes code block when condition evaluates to true.

if (temperature > 30) {

printf("It's hot outside!\n");

}if-else Statement: Provides alternative execution path when condition is false.

if (score >= 60) {

printf("Passed\n");

} else {

printf("Failed\n");

}if-else-if Ladder: Tests multiple conditions sequentially.

if (grade >= 90) {

printf("A\n");

} else if (grade >= 80) {

printf("B\n");

} else if (grade >= 70) {

printf("C\n");

} else {

printf("D\n");

}Nested if Statements: Place if statements inside other if statements for complex logic.

Switch Statement

Switch statements provide elegant multi-way branching based on integer or character expressions:

switch (day) {

case 1:

printf("Monday\n");

break;

case 2:

printf("Tuesday\n");

break;

case 3:

printf("Wednesday\n");

break;

default:

printf("Other day\n");

}The break statement prevents fall-through to subsequent cases. This C programming tutorial emphasizes always including break statements unless fall-through is intentional.

Loop Statements

while Loop: Repeats code block while condition remains true. Checks condition before executing loop body.

int count = 1;

while (count <= 5) {

printf("%d ", count);

count++;

}

// Output: 1 2 3 4 5do-while Loop: Executes loop body at least once, then checks condition. Useful when you need guaranteed first execution.

int num;

do {

printf("Enter positive number: ");

scanf("%d", &num);

} while (num <= 0);for Loop: Compact loop structure ideal when iteration count is known. Contains initialization, condition, and update in one line.

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

printf("%d ", i);

}Nested Loops: Loops inside other loops enable multi-dimensional iterations like processing matrices or generating patterns.

Jump Statements

break: Exits the innermost loop or switch statement immediately, continuing execution after the terminated structure.

continue: Skips remaining code in current loop iteration, proceeding to next iteration.

goto: Transfers control to labeled statement. This C programming tutorial recommends avoiding goto as it reduces code readability, though it has legitimate uses in error handling.

return: Exits function, optionally returning a value to the caller.

Functions and Modular Programming

Functions are fundamental building blocks in C programming tutorial methodology. They promote code reusability, organization, and abstraction.

Understanding Functions

Functions are self-contained code blocks that perform specific tasks. Every C program contains at least one function: main(). Well-designed functions make programs easier to understand, test, and maintain.

Function Declaration and Definition

Function Declaration (Prototype): Informs compiler about function existence, return type, and parameters before actual definition.

Function Definition: Contains actual implementation with function body.

// Function declaration

int add(int a, int b);

// Function definition

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

// Function call

int result = add(10, 20);Function Parameters

Formal Parameters: Variables listed in function definition that receive values.

Actual Parameters (Arguments): Values passed to function during call.

Pass by Value: Default mechanism where function receives copies of arguments. Changes inside function don’t affect original variables.

void increment(int x) {

x++; // Only local copy changes

}

int num = 5;

increment(num); // num still equals 5This C programming tutorial will later cover pass by reference using pointers.

Return Statement

Functions return values using return statement. Return type specified in function declaration must match returned value type. void functions don’t return values.

float calculateAverage(int sum, int count) {

return (float)sum / count;

}Scope and Lifetime

Local Variables: Declared inside functions, accessible only within that function. Created when function executes, destroyed when function returns.

Global Variables: Declared outside all functions, accessible throughout program. Exist for entire program execution.

Static Variables: Retain values between function calls while remaining local in scope.

void counter() {

static int count = 0; // Initialized only once

count++;

printf("%d ", count);

}

counter(); // Output: 1

counter(); // Output: 2

counter(); // Output: 3Recursive Functions

Recursion occurs when functions call themselves, solving problems by breaking them into smaller identical sub-problems. This C programming tutorial emphasizes understanding base cases to prevent infinite recursion.

int factorial(int n) {

if (n <= 1) return 1; // Base case

return n * factorial(n - 1); // Recursive case

}Classic recursive problems include factorial calculation, Fibonacci sequence, tree traversal, and tower of Hanoi.

Function Pointers

Function pointers store addresses of functions, enabling dynamic function calls and callback mechanisms:

int (*operation)(int, int); // Pointer to function returning int

operation = add; // Assign function address

int result = operation(5, 3); // Call through pointerArrays and Strings

Arrays store multiple values of the same type under single variable name. This C programming tutorial section covers array fundamentals and string manipulation.

One-Dimensional Arrays

Arrays are contiguous memory blocks storing fixed-size sequential collections of elements.

Declaration and Initialization:

int numbers[5]; // Declaration

int scores[5] = {85, 90, 78, 92, 88}; // Initialization

int values[] = {1, 2, 3, 4}; // Size automatically determinedAccessing Array Elements: Use zero-based indexing with square brackets. First element is array[0], last element is array[size-1].

int first = scores[0]; // Access first element

scores[2] = 95; // Modify third elementMulti-Dimensional Arrays

Two-dimensional arrays represent matrices or tables:

int matrix[3][4]; // 3 rows, 4 columns

int table[2][3] = {

{1, 2, 3},

{4, 5, 6}

};

int element = table[1][2]; // Access row 1, column 2 (value: 6)Processing multi-dimensional arrays typically requires nested loops.

Array Limitations

Arrays have fixed size determined at declaration. C doesn’t perform automatic bounds checking, so accessing out-of-bounds indices causes undefined behavior. This C programming tutorial stresses careful index management.

Strings in C

C treats strings as character arrays terminated by null character ‘\0’. This null terminator distinguishes strings from plain character arrays.

String Declaration:

char name[20] = "John"; // Automatically null-terminated

char greeting[] = "Hello"; // Size automatically includes null terminator

char message[10]; // Uninitialized string bufferString Input and Output

Reading Strings:

char name[50];

scanf("%s", name); // Reads until whitespace (unsafe for spaces)

fgets(name, 50, stdin); // Safer, reads entire line including spacesDisplaying Strings:

printf("%s", name); // Print string

puts(name); // Print string with automatic newlineString Manipulation Functions

Standard library <string.h> provides essential string functions:

strlen(): Returns string length excluding null terminator strcpy(): Copies source string to destination strcat(): Concatenates (appends) source to destination strcmp(): Compares two strings lexicographically strchr(): Finds first occurrence of character strstr(): Finds first occurrence of substring

#include <string.h>

char str1[20] = "Hello";

char str2[20] = "World";

int length = strlen(str1); // Returns 5

strcpy(str2, str1); // str2 becomes "Hello"

strcat(str1, " World"); // str1 becomes "Hello World"

int result = strcmp(str1, str2); // Returns comparison resultThis C programming tutorial emphasizes using safe string functions like strncpy() and strncat() with size limits to prevent buffer overflows.

Pointers and Memory Management

Pointers are C’s most powerful and complex feature. This essential C programming tutorial section explains pointer fundamentals and memory management.

Understanding Pointers

Pointers are variables that store memory addresses of other variables. They enable dynamic memory allocation, efficient array processing, and complex data structures.

Pointer Declaration:

int *ptr; // Pointer to integer

float *fptr; // Pointer to float

char *cptr; // Pointer to characterAddress and Dereference Operators

Address-of operator (&): Returns memory address of variable

Dereference operator (*): Accesses value at pointer’s address

int num = 42;

int *ptr = # // ptr stores address of num

printf("%d", *ptr); // Prints 42 (value at address)

printf("%p", ptr); // Prints memory address

*ptr = 100; // Changes num to 100Pointer Arithmetic

Pointers support arithmetic operations based on pointed data type size:

int arr[5] = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

int *ptr = arr; // Points to first element

ptr++; // Moves to next integer (4 bytes forward)

int value = *ptr; // value = 20

ptr += 2; // Moves 2 integers forward

value = *ptr; // value = 40Pointers and Arrays

Array names act as constant pointers to first element. This C programming tutorial demonstrates array-pointer relationship:

int numbers[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

int *ptr = numbers; // Equivalent to &numbers[0]

// These are equivalent:

numbers[2];

*(numbers + 2);

ptr[2];

*(ptr + 2);Pointers and Functions

Pass by Reference: Passing pointers allows functions to modify original variables:

void swap(int *a, int *b) {

int temp = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = temp;

}

int x = 10, y = 20;

swap(&x, &y); // x and y are swappedReturning Pointers: Functions can return pointers, but never return addresses of local variables:

int* getMax(int *a, int *b) {

return (*a > *b) ? a : b;

}Dynamic Memory Allocation

Dynamic memory allocation enables runtime memory management using functions from <stdlib.h>:

malloc(): Allocates specified bytes, returns void pointer

int *arr = (int*)malloc(5 * sizeof(int)); // Allocate array of 5 integers

if (arr == NULL) {

printf("Memory allocation failed\n");

return 1;

}calloc(): Allocates memory and initializes to zero

int *arr = (int*)calloc(5, sizeof(int)); // 5 integers initialized to 0realloc(): Resizes previously allocated memory block

arr = (int*)realloc(arr, 10 * sizeof(int)); // Resize to 10 integersfree(): Deallocates previously allocated memory

free(arr); // Release memory

arr = NULL; // Good practice to avoid dangling pointersThis C programming tutorial emphasizes always freeing dynamically allocated memory to prevent memory leaks.

Pointer Safety

Common pointer pitfalls include:

Null Pointers: Always check if malloc/calloc returned NULL before use Dangling Pointers: Pointers referencing freed memory Memory Leaks: Forgetting to free allocated memory Buffer Overflows: Writing beyond allocated memory bounds Uninitialized Pointers: Using pointers before assigning valid addresses

Structures and Unions

Structures and unions enable creating complex data types by grouping related variables. This C programming tutorial section covers user-defined data structures.

Also Read: How to Become a Programmer

Structures

Structures (structs) are composite data types containing multiple variables of different types under single name.

Structure Definition:

struct Student {

char name[50];

int rollNumber;

float marks;

};Declaring Structure Variables:

struct Student student1; // Declaration

struct Student student2 = {"Alice", 101, 85.5}; // Declaration with initializationAccessing Structure Members:

strcpy(student1.name, "Bob");

student1.rollNumber = 102;

student1.marks = 90.0;

printf("Name: %s\n", student1.name);

printf("Roll: %d\n", student1.rollNumber);Typedef with Structures

typedef creates aliases for data types, simplifying structure declarations:

typedef struct {

int x;

int y;

} Point;

Point p1, p2; // No need for 'struct' keyword

p1.x = 10;

p1.y = 20;Nested Structures

Structures can contain other structures as members:

typedef struct {

int day;

int month;

int year;

} Date;

typedef struct {

char name[50];

Date birthDate;

float salary;

} Employee;

Employee emp;

emp.birthDate.day = 15;

emp.birthDate.month = 8;

emp.birthDate.year = 1990;Structures and Pointers

Pointers to structures use arrow operator (->) for member access:

Employee *ptr = &emp;

strcpy(ptr->name, "John");

ptr->salary = 50000.0;

// Equivalent to:

strcpy((*ptr).name, "John");Structures and Functions

Pass structures to functions by value or pointer. This C programming tutorial recommends passing large structures by pointer for efficiency:

void displayEmployee(Employee *e) {

printf("Name: %s\n", e->name);

printf("Salary: %.2f\n", e->salary);

}

displayEmployee(&emp);Arrays of Structures

Create collections of structured data:

Employee company[100]; // Array of 100 employees

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

scanf("%s", company[i].name);

scanf("%f", &company[i].salary);

}Unions

Unions allow storing different data types in same memory location. Only one member holds value at any time.

union Data {

int intValue;

float floatValue;

char charValue;

};

union Data data;

data.intValue = 42;

printf("%d\n", data.intValue);

data.floatValue = 3.14; // Overwrites intValue

printf("%f\n", data.floatValue);Unions are memory-efficient when only one member is needed at a time. This C programming tutorial notes unions are common in embedded systems and networking.

Bit Fields

Bit fields allow specifying exact number of bits for structure members:

struct Flags {

unsigned int flag1 : 1; // 1 bit

unsigned int flag2 : 1; // 1 bit

unsigned int value : 6; // 6 bits

};Bit fields optimize memory usage for boolean flags and small integer ranges.

File Handling in C

File operations enable persistent data storage and retrieval. This C programming tutorial section covers comprehensive file handling techniques.

File Operations Overview

File handling involves opening files, performing operations (reading/writing), and closing files. Functions reside in <stdio.h>.

Opening Files

fopen() function:

FILE *fptr;

fptr = fopen("filename.txt", "mode");

if (fptr == NULL) {

printf("Error opening file\n");

return 1;

}File Modes:

- “r”: Read mode (file must exist)

- “w”: Write mode (creates new file or truncates existing)

- “a”: Append mode (adds to end of file)

- “r+”: Read and write mode

- “w+”: Write and read mode

- “a+”: Append and read mode

Add “b” for binary file operations: “rb”, “wb”, “ab”

Reading from Files

Character Input:

int ch;

while ((ch = fgetc(fptr)) != EOF) {

putchar(ch);

}String Input:

char buffer[100];

while (fgets(buffer, 100, fptr) != NULL) {

printf("%s", buffer);

}Formatted Input:

int num;

float value;

fscanf(fptr, "%d %f", &num, &value);Binary Read:

Student students[10];

fread(students, sizeof(Student), 10, fptr);Writing to Files

Character Output:

char ch = 'A';

fputc(ch, fptr);String Output:

fputs("Hello, World!\n", fptr);Formatted Output:

fprintf(fptr, "Name: %s, Age: %d\n", name, age);Binary Write:

fwrite(students, sizeof(Student), 10, fptr);Closing Files

Always close files after operations to flush buffers and release resources:

fclose(fptr);File Position Functions

Control file position indicator for random access:

fseek(): Moves file pointer to specific location

fseek(fptr, 0, SEEK_SET); // Beginning of file

fseek(fptr, 0, SEEK_END); // End of file

fseek(fptr, 100, SEEK_CUR); // 100 bytes from current positionftell(): Returns current file position

long position = ftell(fptr);rewind(): Moves file pointer to beginning

rewind(fptr); // Equivalent to fseek(fptr, 0, SEEK_SET)Error Handling in File Operations

feof(): Checks if end of file reached

ferror(): Checks if error occurred during file operations

if (ferror(fptr)) {

printf("Error during file operation\n");

}This C programming tutorial emphasizes proper error checking for robust file handling applications.

Practical File Handling Example

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

FILE *sourceFile, *destFile;

char ch;

sourceFile = fopen("source.txt", "r");

destFile = fopen("destination.txt", "w");

if (sourceFile == NULL || destFile == NULL) {

printf("Error opening files\n");

return 1;

}

while ((ch = fgetc(sourceFile)) != EOF) {

fputc(ch, destFile);

}

printf("File copied successfully\n");

fclose(sourceFile);

fclose(destFile);

return 0;

}Advanced C Programming Concepts

This section of our C programming tutorial explores sophisticated techniques used in professional development.

Preprocessor Directives

The C preprocessor modifies source code before compilation.

Macro Definitions:

#define PI 3.14159

#define MAX(a,b) ((a) > (b) ? (a) : (b))

#define SQUARE(x) ((x) * (x))Conditional Compilation:

#ifdef DEBUG

printf("Debug mode enabled\n");

#endif

#ifndef VERSION

#define VERSION 1.0

#endif

#if defined(WINDOWS)

// Windows-specific code

#elif defined(LINUX)

// Linux-specific code

#else

// Generic code

#endifFile Inclusion:

#include <stdio.h> // Standard library header

#include "myheader.h" // User-defined headerMacro Operations:

#undef MACRO_NAME // Undefine macro

#pragma directive // Compiler-specific commandsCommand Line Arguments

Programs can accept arguments from command line:

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("Program name: %s\n", argv[0]);

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

printf("Argument %d: %s\n", i, argv[i]);

}

return 0;

}argc: Argument count (number of arguments) argv: Argument vector (array of string pointers)

Enumeration

Enumerations define named integer constants:

enum Color {RED, GREEN, BLUE}; // RED=0, GREEN=1, BLUE=2

enum Status {SUCCESS = 1, FAILURE = -1, PENDING = 0};

enum Color favoriteColor = GREEN;

if (favoriteColor == GREEN) {

printf("Green is selected\n");

}Enumerations improve code readability compared to magic numbers.

Storage Classes

Storage classes define scope, lifetime, and visibility of variables:

auto: Default for local variables, automatic storage duration

register: Suggests storing variable in CPU register for faster access

register int counter; // Frequently used variablestatic: Preserves variable value between function calls, limits scope to file

static int callCount = 0; // Retains value across callsextern: Declares variable defined in another file

extern int globalVar; // Defined elsewhereThis C programming tutorial notes proper storage class usage optimizes performance and organization.

Variable Arguments Functions

Functions accepting variable number of arguments use <stdarg.h>:

#include <stdarg.h>

int sum(int count, ...) {

va_list args;

va_start(args, count);

int total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

total += va_arg(args, int);

}

va_end(args);

return total;

}

int result = sum(4, 10, 20, 30, 40); // Returns 100Multi-file Programs

Large projects split code across multiple files:

header.h:

#ifndef HEADER_H

#define HEADER_H

int add(int a, int b);

void display();

#endiffunctions.c:

#include "header.h"

int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

void display() {

printf("Hello from functions.c\n");

}main.c:

#include "header.h"

int main() {

int result = add(5, 3);

display();

return 0;

}Compile with: gcc main.c functions.c -o program

Type Qualifiers

const: Creates read-only variables

const int MAX = 100;

const int *ptr; // Pointer to constant integer

int *const ptr2; // Constant pointer to integer

const int *const ptr3; // Constant pointer to constant integervolatile: Indicates variable may change unexpectedly (hardware registers, shared memory)

volatile int sensorValue; // May change outside program controlrestrict: Pointer optimization hint (C99 and later)

void process(int *restrict ptr);Best Practices and Optimization

Professional C programming tutorial guidance emphasizes code quality, maintainability, and performance.

Coding Standards

Naming Conventions:

- Use descriptive variable names:

studentCountinstead ofsc - Constants in UPPERCASE:

MAX_SIZE,PI - Functions in camelCase or snake_case:

calculateAverage()orcalculate_average() - Avoid single-letter names except loop counters

Code Formatting:

- Consistent indentation (2 or 4 spaces)

- Opening braces on same or next line consistently

- Spaces around operators:

a + bnota+b - One statement per line

- Blank lines to separate logical sections

Comments and Documentation:

- Explain why, not what (code shows what)

- Update comments when code changes

- Document function parameters and return values

- Use header comments for files and functions

/**

* Calculates the average of an array of integers

*

* @param arr Array of integers

* @param size Number of elements in array

* @return Average value as float

*/

float calculateAverage(int arr[], int size) {

if (size == 0) return 0.0;

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

sum += arr[i];

}

return (float)sum / size;

}Memory Management Best Practices

Always free allocated memory:

int *ptr = malloc(100 * sizeof(int));

if (ptr != NULL) {

// Use ptr

free(ptr);

ptr = NULL; // Avoid dangling pointer

}Check allocation success:

void *ptr = malloc(size);

if (ptr == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "Memory allocation failed\n");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}Avoid memory leaks:

- Free memory in same scope where allocated when possible

- Use tools like Valgrind to detect leaks

- Match every malloc/calloc with corresponding free

Performance Optimization

Algorithm Selection: Choose efficient algorithms before micro-optimizations. O(n log n) algorithm beats optimized O(n²) for large datasets.

Loop Optimization:

// Instead of calling strlen() repeatedly

int len = strlen(str);

for (int i = 0; i < len; i++) {

// Process str[i]

}

// Better: Cache frequently used valuesInline Functions: For small frequently-called functions, consider inline suggestion:

inline int square(int x) {

return x * x;

}Use appropriate data types: Don’t use long long when int suffices. Smaller types save memory and cache space.

Compiler Optimization: Enable optimization flags:

-O2: Moderate optimizations-O3: Aggressive optimizations-Os: Optimize for size

Error Handling

Check function return values:

FILE *file = fopen("data.txt", "r");

if (file == NULL) {

perror("Failed to open file");

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}Use meaningful error messages:

if (divisor == 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Division by zero in function %s\n", __func__);

return -1;

}Clean up resources on errors:

FILE *file = fopen("data.txt", "r");

if (file == NULL) return -1;

int *data = malloc(100 * sizeof(int));

if (data == NULL) {

fclose(file); // Clean up before returning

return -1;

}

// Use file and data

free(data);

fclose(file);Security Considerations

Buffer Overflow Prevention:

// Unsafe

char buffer[10];

gets(buffer); // Never use gets()

// Safe

fgets(buffer, sizeof(buffer), stdin);Input Validation:

int age;

printf("Enter age: ");

if (scanf("%d", &age) != 1) {

printf("Invalid input\n");

return 1;

}

if (age < 0 || age > 150) {

printf("Age out of valid range\n");

return 1;

}Avoid format string vulnerabilities:

// Unsafe

printf(userInput);

// Safe

printf("%s", userInput);This C programming tutorial emphasizes security awareness prevents common vulnerabilities.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Learning from common errors accelerates C programming mastery. This C programming tutorial section highlights frequent pitfalls.

Array Index Errors

Off-by-one errors:

int arr[10];

for (int i = 0; i <= 10; i++) { // Wrong! Should be i < 10

arr[i] = i; // Writes beyond array bounds

}Negative indices:

Arrays cannot have negative indices in standard C. Using them causes undefined behavior.

Pointer Mistakes

Dereferencing NULL pointers:

int *ptr = NULL;

*ptr = 10; // Crash! Always check for NULL firstDangling pointers:

int *ptr = malloc(sizeof(int));

free(ptr);

*ptr = 5; // Undefined behavior! Accessing freed memoryUninitialized pointers:

int *ptr; // Points to random memory

*ptr = 10; // Undefined behaviorString Handling Errors

Missing null terminator:

char str[5] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o'}; // No null terminator

printf("%s", str); // Undefined behaviorBuffer overflow in string operations:

char dest[5];

strcpy(dest, "Hello World"); // Buffer overflow!

// Use safe version

strncpy(dest, "Hello World", sizeof(dest) - 1);

dest[sizeof(dest) - 1] = '\0';Memory Leaks

Forgetting to free:

void function() {

int *ptr = malloc(100 * sizeof(int));

// Forgot to free before return

return; // Memory leak!

}Losing pointer to allocated memory:

int *ptr = malloc(100 * sizeof(int));

ptr = malloc(200 * sizeof(int)); // Lost reference to first allocationComparison Mistakes

Assignment in conditions:

int x = 5;

if (x = 0) { // Assigns 0 to x, then evaluates to false

printf("This won't print\n");

}

// Should be:

if (x == 0) { // ComparisonFloating-point equality:

float a = 0.1 + 0.2;

if (a == 0.3) { // May fail due to precision

// Use epsilon comparison instead

}

// Better:

#define EPSILON 0.0001

if (fabs(a - 0.3) < EPSILON) {Scope Issues

Returning address of local variable:

int* getNumber() {

int num = 42;

return # // Wrong! Local variable destroyed

}Static array initialization issues:

int* createArray() {

static int arr[10]; // Shared across all calls

// Initialize arr

return arr;

}Undefined Behavior

Modifying string literals:

char *str = "Hello";

str[0] = 'h'; // Undefined behavior! String literals are read-onlySigned integer overflow:

int max = INT_MAX;

max++; // Undefined behaviorSequence point violations:

int i = 5;

int result = i++ + ++i; // Undefined behaviorThis comprehensive C programming tutorial prepares developers to write robust, efficient code by understanding and avoiding these pitfalls.

Conclusion

This extensive C programming tutorial has covered fundamental through advanced concepts, providing a solid foundation for C development. From basic syntax and data types to complex topics like pointers, memory management, and file handling, you now possess comprehensive knowledge to build efficient C applications.

C programming remains essential for system programming, embedded development, and performance-critical applications. The concepts learned in this C programming tutorial form the backbone of modern software development, influencing numerous contemporary programming languages.

Next Steps in Your C Programming Journey

Practice Regularly: Implement programs covering topics from this C programming tutorial. Start with simple projects and gradually increase complexity.

Explore Standard Library: Familiarize yourself with standard library functions beyond those covered here. Understanding available tools prevents reinventing the wheel.

Study Open Source Code: Examine well-written C projects on platforms like GitHub to learn professional coding practices and design patterns.

Build Projects: Create practical applications such as file utilities, data structure implementations, simple games, or command-line tools.

Learn Data Structures and Algorithms: Apply C programming skills to implement fundamental data structures (linked lists, trees, graphs) and algorithms (sorting, searching, dynamic programming).

Explore Advanced Topics: Dive deeper into multithreading, network programming, database connectivity, and system programming as you gain confidence.

Join Communities: Participate in C programming forums, Stack Overflow, and developer communities to share knowledge and learn from experienced programmers.

Key Takeaways from This C Programming Tutorial

C programming mastery requires understanding low-level concepts, memory management, and efficient algorithm implementation. The language’s simplicity combined with powerful features makes it both challenging and rewarding to learn.

Success in C programming comes from:

- Writing clean, readable, and maintainable code

- Understanding memory and pointer mechanics thoroughly

- Following best practices and coding standards

- Regular practice and continuous learning

- Debugging skills and attention to detail

Resources for Continued Learning

Books:

- “The C Programming Language” by Kernighan and Ritchie

- “C Programming: A Modern Approach” by K. N. King

- “Expert C Programming” by Peter van der Linden

Online Platforms:

- Official C documentation and standards

- Programming challenge websites (HackerRank, LeetCode)

- Tutorial websites and video courses

- University course materials and MOOCs

Development Tools:

- Debuggers (GDB, LLDB)

- Memory analysis tools (Valgrind)

- Static analysis tools (Clang Static Analyzer)

- Integrated development environments

This C programming tutorial provides the knowledge foundation for your programming career. Whether you’re pursuing embedded systems, operating system development, or simply want to understand how computers work at a fundamental level, C programming skills prove invaluable.

Remember that becoming proficient takes time and consistent effort. Review difficult concepts, experiment with code, make mistakes, and learn from them. Every expert programmer was once a beginner who refused to give up.

Thank you for following this comprehensive C programming tutorial. Your journey into the world of efficient, powerful, and elegant programming starts here. Write code, build projects, solve problems, and most importantly, enjoy the process of becoming a skilled C programmer.

Start coding today, and transform your programming aspirations into reality with the timeless power of C programming!